Parallel, Distributed and Multiagent Production Systems

License: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Multiagent Systems. Copyright © 1995, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.Editor: First International Conference on Multiagent Systems. Copyright © 1995, AAAI (www.aaai.org).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-58698-9

URL: https://www.aaai.org/Papers/ICMAS/1995/ICMAS95-056.pdf

Last revision: 2022/08/21

Citation: Ishida, T. (1994). Parallel, Distributed and Multiagent Production Systems (Vol. 878). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-58698-9

Cite control: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27.

A Research Foundation for Distributed Artificial Intelligence

Abstract: Production systems have been widely used as expert system building tools and recognize-and-act models in cognitive science. This paper is intended to introduce parallel/distributed/multi agent production systems, and to reveal their possibilities as research foundations for dis tributed artificial intelligence: a parallel produc tion system as an agent reactive architecture; a distributed production system as an adaptive agent organization; and a multi-agent production system for organizational learning. Production systems already have been equipped with clear syntax/semantics and efficient pattern match ing algorithms. Their functions can be further strengthened with recent algorithms such as real time search and reinforcement learning.

Keywords: multi-agent production systems; expert systems building tools, synchronous paralell prduction system; asynchronous parallel production systems

1. Introduction

Production systems have been studied as a cognitive model for humans or intelligent agents. Since the input-output relation in each rule is clearly described, production systems attract people who need a language for describing non-deterministic decision making pro ceases. Once Forgy implemented a high speed pattern matching algorithm [Forgy, 1982]5, production systems became the most popular expert system building tool.

With the success of expert systems (eg. XCON), researchers started working on parallel processing to improve the performance of production systems. Be cause 90% of the processing time is consumed by pat tern matching, parallel matching was studied first. The author is, however, more interested in executing rules concurrently. Concurrent production systems can be classified into three categories:

-

Synchronous parallel production systems or parallel rule firing [Ishida and Stolfo, 1985; Ishida, 1991]11,14, where rules are fired in parallel to reduce the total number of sequential production cycles, while rule firings are globally synchronized in each production cycle.

-

Asynchronous parallel production systems or distributed production systems [Ishida et aL, 1990; 1992; Gasser and Ishida, 1991]13,19,6, where rules are distributed among multiple processes, and fired in parallel with out global synchronization.

-

Multiagent production systems [lshida, 1992b]18, where multiple production system programs com pete or cooperate to solve a single problem or mul tiple problems.

Since production systems have been utilized for de scribing static knowledge, people feel that production systems are not suited to dynamically handle real world problems. The aim of this paper is to show the possibilities of concurrent production systems as a re search foundation for distributed artificial intelligence.

Our intuition is that a collection of production systems could be a model of a dynamic human society, since each production system can represent the recognize and-act cycle of an individual human. The remainder of this paper reveals their potential abilities for solv ing dynamic real-world problems: a parallel production system as an agent reactive architecture, a distributed production system as an adaptive agent organization, and a multi-agent production system for organizational learning.

2. Production Systems Revisited

It was probably unfortunate that the first success ful production systems was the XCON expert system, which can create an optimal configuration of fairly complex computer systems [Soloway et al., 1987]25. The success resulted in the unreasonable expectation that “production systems can solve complex problems with out describing procedures.” However, this was mislead ing. Unlike Prolog, production systems have no back tracking mechanism. A production system refers to a working memory which represents an actual world, finds rules which can be fired, and selects one rule to change the working memory. When backtracking is needed, reverse actions have to be executed. If no re verse action is available, there is no way to recover the situation. Recall the famous “monkey and bananas” example. This example shows how difficult it is for a production system to create a sequence of actions (i.e., plans). Production systems are inherently suited to execute stimulus-response type rules, but ate not powerful enough to produce complex procedures.

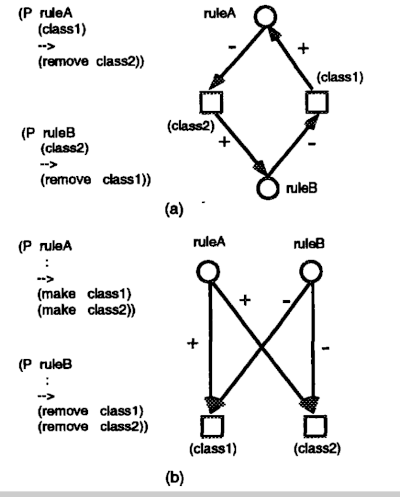

Figure 1. Controlling Rule Firings

Rule: (P ruleA (class1)

-->

(make class2)

(remove clasa1))

(P ruleB (class1)

:

Plan-1: (dotimes (i 100) (? ruleA))

Plan-2: (loop (select ((? ruleA))

((? ruleB))

((? ruleC))

(otherwise (return))))

Then, how to constrain selfish rule firings? One way is to introduce procedural control description [Ishida et al., 1991; 1995].16–20. The key idea is to view production systems as a collection of independent rule processes, each of which monitors a working memory and per forms actions when its conditions are satisfied by the working memory. Procedural control macros, which are based on Hoare’s CSP [Hoare, 1978]8, can then be introduced to establish communication links between the meta-level control processes and the collection of rule processes.

Figure 1 represents a coding example. Since rules can .be viewed as independent processes, the ~.-macro, which is based on the CSP input command, is intro duced to invoke a single rule. This macro executes the specified rule, when the conditions of the rule are sat isfied. Otherwise the .~-macro monitors the working memory and waits for data changes until the conditions of the rule are satisfied. Plan-1 shown in Figure 1 is written using the ?-macro and the dotimes macro of Lisp.

The production system interpreter tests the left hand sides of multiple rules simultaneously and selects one executable rule through conflict resolution. For viewing control plans as a natural extension of con ventional production system interpreters, the rule selection macro (select-macro) is created, which is influenced by the CSP guarded command and alternative command. The interpreter for three rules can be expressed as Plan~2 in Figure 1 by using select-macro. This control plan repeatedly executes the three rules until no rule can be fired. Since control macros can appear at any place in Lisp programs, conventional production system interpreters can be easily extended and can invoke them from anywhere in the control plans.

There is another way to constrain rule firings: introduce a learning mechanism into production systems. Holland proposed a reinforcement learning mechanism called becket brigade [Holland, 1986]9, which distributes a success award not only to the latest rule but also to the rules executed before. It strengthens the sequence of rules that leads to success. From the problem solving point of view, however, the work does not provide any concrete result: we do not know what class of problems can be solved by this mechanism. Q-learning [Watkins, 1989]26 is similar, but can guarantee convergence to the best policy that maximizes expected rewards. Real time search [Koff, 1990; Ishida and Korf 1991; Ishida 1992a]21,15,17 is also capable of learning the best plan through repeatedly solving the given problem. The relation ship between Q-learning and realtime search was clar ified by [Barto et al., 1993]1. Surprising enough, even though the backgrounds of these researchers are to tally different, both algorithms are based on the same mechanism, dynamic programming, and solve problems in only slightly different ways.

For example, suppose we have a robot in a large maze. The robot can move right, left, back and forth. If the robot can identify its state (eg. zy-axis), these algorithms incrementally learn the optimal action se quences to escape from the maze. Q-learning is ap plicable when the probabilities of state transitions are unknown. Otherwise, realtime search is more efficient. Production systems can provide logic level description of states to these learning algorithms.

2.1. Parallel Production Systems for Reactive Behavior

A production system can be seen as a set of rules, each of which monitors the working memory. Once the precondition is satisfied, each rule tries to fire itself. In sequential production systems, however, the conflict resolution mechanism selects just one of the rules, so that rules are fired sequentially. On the other hand, in parallel production systems, we concurrently execute as many rules as possible [Ishida and Stolfo, 1985]. The fundamental problem in parallel rule firing is how to guarantee the serializability of rule firings. Interference analysis is introduced to detect cases where a parallel firing result differs from the result of sequential firings of the same rules in any order.

To analyze the interference among multiple rule in stantiations of production rules, a data dependency graph of production systems is introduced, which is constructed from the following primitives: a production node (a P-node show as a circle in the figures), which represents a set of instantiations, a working memory node (a W-node shown as a square), which represents a set of working memory elements, a directed edge from a P-node to a W-node, which represents the fact that a P-node modifies a W-node, and a directed edge from a W-node to a P-node, which represents the fact that a P-node refers to a W-node.

For example, in Figure 2(a), suppose two work ing memory elements initially exist: (class1) and (class2). If rules are fired sequentially, there remains (class1) when ruleA is first executed, or (class2) …

Figure 2. Interferences among Rules

when ruleB is first executed. However, if the two rules are fired in parallel, there remains no working memory element. Figure 2(b) considers the case where there no working memory element before execution. If the rules are fired sequentially, there remains no working memory element when ruleA is first executed, or there remains two working memory elements, (class1) and (class2), when ruleB is executed first. If the rules are fired in parallel, however, there are four possibil ities, i.e., (class1) and (class2) remain, (class1) remains, (class2) remains, or no working memory el ement remains.

Based on a data dependency graph of produc tion systems, general techniques applicable to both compile- and run-time analyses are provided. Two al gorithms are then proposed to realize the parallel rule firings on actual multiple processor systems: An effi cient selection algorithm is provided to select multiple rules to be fired in parallel by combining the compile and run-time interference analysis techniques. The de composition algorithm partitions the given production system program and applies the partitions to paral lel processes. A parallel programming language is also provided to allow programmers to make full use of the potential parallelism without considering the internal parallel mechanism.

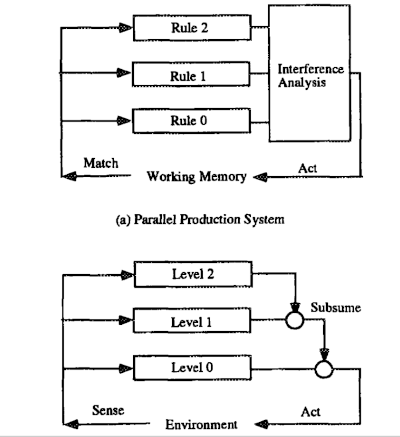

Figure 3. Reactive Architectures

Let us compare the architectures of parallel produc tion systems and a subsumption architecture [Brooks, 1986]2. Figure 3(a) illustrates parallel production sys tems, while Figure 3(b) represents the subsumption architecture considered. The difference between them is the role of mediators. In parallel production systems, the centralized mediator detects and avoids interfer ences among rules. In the subsumption architecture, the distributed mediator inhibits the lower level ac tivities. Since, the mediator could be distributed in parallel production systems [Ishida, 1991]14, there is no serious difference among them. By generalizing the mediator’s process, a parallel production system can represent systems based on a subsumption architec ture.

2.2. Distributed Production Systems for Organizational Adaptation

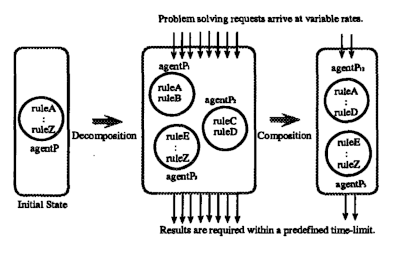

For the asynchronous execution of production systems: parallel rule firing, with global control, is extended to distributed rule firing; problems are solved by a soci ety of production system agents using distributed con trol. Organization self-design is then introduced into the distributed production systems to provide adap tive work allocation. In our model, problem-solving requests issued from the environment arrive at the or ganization continuously, and at variable rates. To re spond, the organization must supply meaningful re suits within specified time limits. Two reorganization primitives, composition and decomposition, are newly introduced. These primitives change the number of production systems and the distribution of rules in an organization.

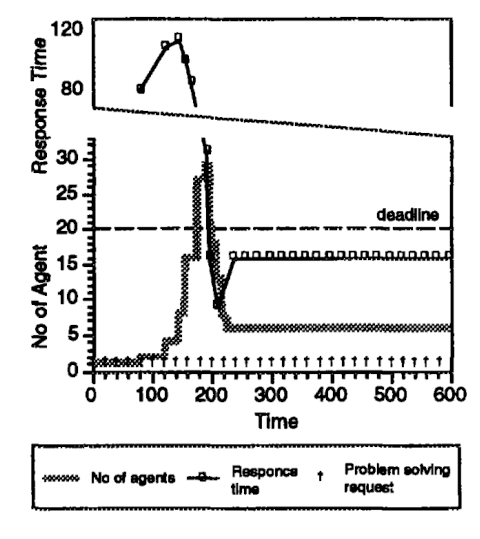

Figure 4. Organization Adaptation

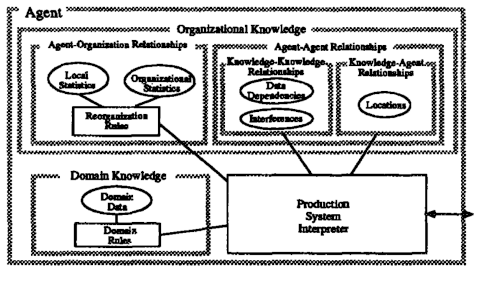

Figure 5. Production System Agent

Organization self-design is useful when real-time constraints exist and production systerm have to adapt to changing environmental requirements. When over loaded, individual agents decompose themselves to in crease parallelism, and when the load lightens the agents combine with each other to free extra hardware resources. Figure 4 shows the behavior of organiza tional adaptation.

No single organization can adequately handle all problems and environmental conditions. For example, suppose there are three agents in an organization, each of which fires one production rule for solving each prob lem request, the three agents work in a pipelined fash ion (because their rules are sequentially dependent), and the communication delay among agents is equal to one production cycle. Thus, the total throughput cycle time for satisfying a single request is 5. In this case, however, a single agent organization would per form better because of reduced communication over head; it would take only 3 cycles for satisfying a single request. On the other hand, if there were ten problem solving requests, the response time of the last request would be 14 cycles in the three agent organization, while it would be 30 in the single agent case. A production system agent is a production system ca pable of interacting with other agents. As illustrated in Figure 5, the production system agent consists of a production system interpreter and domain knowledge, which includes domain rules and domain data. Note that each agent contains a part of the domain knowl edge. To perform domain problem solving in a dis tributed fashion, the agents need organizational knowl edge, which represents both the necessary interactions among agents and their organization. Organizational knowledge is initially obtained by analyzing domain knowledge at compile time, and are dynamically main rained during the process of organization self-design.

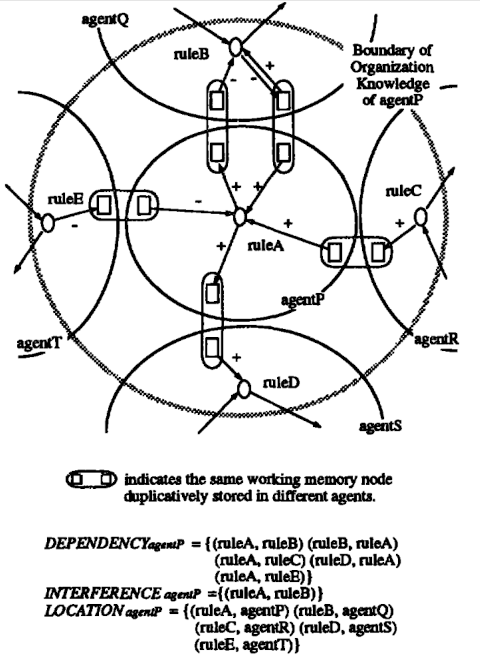

Since agents asynchrononsly perform reorganization, organizational knowledge can be temporarily inconsis tent across agents. Organizational knowledge is further classified into several categories. Agent-agent relationships can be seen as the aggregation of two more primitive types of relationships: knowledge-knowledge relationships, which represent interactions within domain knowl edge, and knowledge-agent relationships which rep resent how domain knowledge is distributed among agents. Knowledge-knowledge relationships consist of data dependencies and interferences among domain rules. An agent that has such a knowledge-knowledge relationship with a particular agent is called that agent’s neighbor. Figure 6 illustrates agent-agent re lationships.

For appropriate reorganization, the organizational knowledge includes agent-organization relationships, which represent how agents’ local decisions affect or ganizational behavior. In our case, agent-organization relationships consist of local statistics, organizational statistics and reorganization rules. Since the reorga nization rules are also production rules, organization self-design and domain problem solving are arbitrar ily interleaved. Since multiple agents asynchronously fire rules and perform reorganization, knowing the ex act status of the entire organization is difficult. Under the policy of obtaining better decisions with maximal locality, local and organizational statistics, which can be easily obtained, are first introduced, and then re organization rules using those statistics are provided to select an appropriate reorganization primitive when necessary.

Figure 7 shows the evaluation results. In this figure, communication and reorganization overheads are ignored. The line chart indicates response times normalized by production cycles. The step chart represents the number of agents in the organization. The time limit is set at 20 production cycles, while the measurement period is set at 10 production cycles. In Figure 7, problem solving requests arrive at constant intervals. Around time 100, the response time far exceeds the time limit. Thus the organization starts decomposition. Around time 200, the number of agents has increased to 26, the response time drops below the time limit, and the organization starts composition. After fluctuating slightly, the organization finally reaches a stable state with the number of agents settling at 6. Since composition and decomposition have been interleaved, the firing ratios of the resulting agents are almost equal. This chart show that the society of agents has gradually adapted to the situation through repeated reorganization.

Figure 6. Organizational Knowledge

2.3 Multi-Agent Production Systems for Organizational Learning

Multiagent production systems are interacting multi ple independent production systems, and thus are dif ferent from parallel or distributed production systems. A transaction modelwas thus introduced to achieve ar bitrary interleaved rule firings of multiple production system agents [Ishida, 1992b]18. As a result of allow ing interleaved rule firings, however, ensuring serializability is no longer sufficient to guarantee the consis tency of the shared working memory information.

Figure 7. Performance Evaluation

A logical dependency model and its maintenance mechanisms such as DTMS (Distributed Truth Maintenance System) [Huhns and Bridgeland, 1991]10 or distributed constraint satisfaction algorithms [Yokoo et al., 1992]27 have been introduced to overcome this problem.

The issue of control becomes more and more serious in multiagent production systems. Because various events occur asynchronously in a multiagent network, the agents must cooperatively control their rule execution processes. A meta-level control architecture was then required to prioritize rule firing, to focus the attention of multiple agents on the most urgent tasks. This architecture has been applied to construct a multiagent system called CoCo [Ishida, 1989]12, which con currently performs cooperative operations such as public switched telephone network control.

From the above research, we realized the importance of describing inter-agent protocols. Conventional telecommunication protocols have been studied to guarantee the performance and transparency of data communications. The protocols developed so far are mainly for lower layers (lower than the transport layer), and thus users have not been required to design and verify protocols they used. However, what we need now is an inter-agent protocol to integrate various application programs independently designed by different users. Kuwabara has been developing a language called AgenTalk for describing coordination protocols for multi~gent systems [Kuwabara, 1995; Kuwabara et al., 1995]23,22.

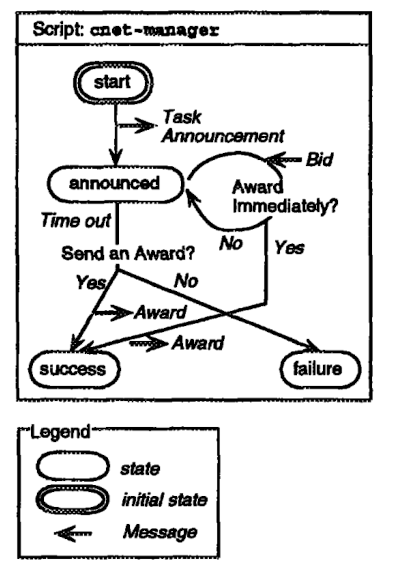

Figure 8. AgenTalk [Kuwabara et al., 1995]22

In AgenTalk, inter-agent protocols are defined by finite state autonmata. Using AgenTalk, Kuwabara describes the behavior of the manager following the contract net protocol. Task allocation in the contract net protocol is performed as follows: First, a manager with a task to be executed broadcasts a Task Announcement message. A contractor that is willing to execute the announced task sends a Bid message. The man ager selects a contractor to which the task is to be allocated and sends an Award message to it. The man ager script arise-manager is shown in Figure 8. The cnet-manager script is supposed to be invoked when the task to be allocated is generated.

Though the finite state automata approach for de scribing protocols is common in a distributed computing community, realtime artificial intelligence people pointed out the similarity of AgenTalk and PRS (Procedural Reasoning System) [Georgeff and Lan sky, 1987]7. In our view, both systems are based on the same state transition framework: PRS describes the interaction between an agent and an environment, while AgenTalk describes the protocol among multiple agents.

AgenTalk is designed to describe various inter-agent protocols. The key feature of AgenTalk is the in heritance mechanism of protocol description. Using AgenTalk, we have described the multistage negotiation protocol [Conry at al., 1991]4 as an extension of the contract-net protocol [Smith, 1980]24. Many application specific coordination protocols are expected to appear soon as software agents are built. AgenTalk is designed to allow various protocols to be defined incrementally and to be easily customized to application domains by incorporating an inheritance mechanism. However, introducing inheritance mechanisms into protocol description generates new technical problems: for example, how to verify the customized protocol, when the original protocol has been verified.

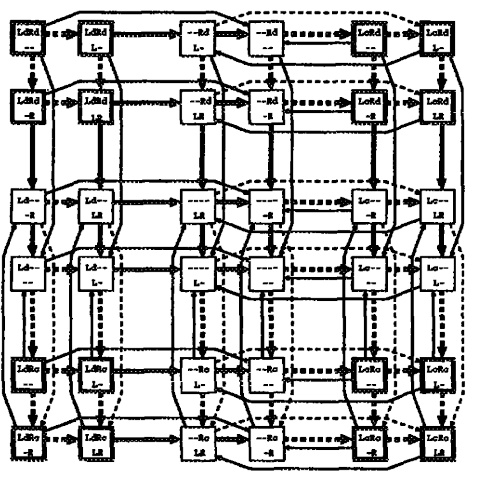

Figure 9. State Space for Dining Philosophers

A more interesting approach is to introduce machine-learning techniques into inter-agent protocols. Some classes of distributed algorithms can be represented by state transition diagram. Let us start with the famous “dining philosophers,” based on Chandy and Misra’s algorithm [Chandy and Misra, 1988]3. Figure 9 illustrates the state transition diagram of a hungry philosopher. Each box represents a philosopher’s state. Upper line indicates whether a philosopher possesses L(left) and R(right) forks, and whether each fork is e(clean) or d(dirty). Lower line indicates whether a philosopher receives a request from L(left) and R(right) neighbors. There are two kinds of state transitions: active and passive. The former is triggered by the philosopher himself. However, the latter is triggered by neighboring philosophers, and thus the probabilities of state transitions are not known at the beginning. In Figure 9, solid edges represent active transitions, and dashed edges represent passive transitions. The state transitions allowed by Chandy and Misra’s algorithm are represented by thick edges. The challenge here is to learn the state transitions represented by thick edges through repeatedly interacting with other philosophers. Reinforcement learning algorithms such as Q-learning can be basis for solving this problem.

Conclusion

Though concurrent production systems were first investigated for performance improvement, they can provide fruitful research basis for distributed artificial intelligence. A parallel production system can describe reactive architectures through generalizing its mediator. A distributed production system can be a research testbed for an adaptive agent organization. A multiagent production system also provides a clear foundation for organizational learning. Protocols are first represented by a set of reactive rules, and then gradually fitted to their execution environments. Introducing protocol learning offers us an avenue towards flexible distributed systems.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks L. Gasser, K. Kuwabara, M. Yokoo and T. Sugimoto for their contribution to this work.

References

-

[Barto et al., 1993] A. G. Barto, S. J. Bradtke and S. P. Singh, “Learning to Act Using Real-Time Dy namic Programming,” UMASS Tech Rep., 1993. ↩ ↩2

-

[Brooks, 1986] R. A. Brooks, “A Robust Layered Con trol System for a Mobile Robot,” IEEE Trans. RA, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1986. ↩ ↩2

-

[Chandy and Misra, 1988] K. M. Chandy and J. Misra, Parallel Program Design, Addison-Wesley, 1988. ↩ ↩2

-

[Conry at ai., 1991] S. E. Conry, K. Kuwabara, V. R. Lesser and R. A. Meyer, “Multistage Negotiation for Distributed Constraint Satisfaction,” IEEE Trans. SMC, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 1462-1477, 1991. ↩ ↩2

-

[Forgy, 1982] C. L. Forgy, “RETE: A Fast Algorithm for the Many Pattern / Many Object Pattern Match Problem,” Artificial Intelligence, Voi. 19, pp. 17-37, 1982. ↩ ↩2

-

[Gasser and Ishida, 1991] L. Gasser and T. Ishida, “A Dynamic Organizational Architecture for Adaptive Problem Solving,” AAAI-91, pp. 185-190, 1991. ↩ ↩2

-

[Georgeff and Lansky, 1987] M. P. Georgeff and A. L. Lansky, “Reactive Reasoning and Planning,” AAAI 87, pp. 677-682, 1987. ↩ ↩2

-

[Hoare, 1978] C. A. R. Hoare, “Communicating Se quential Processes,” CACM, Vol. 21, No. 8, pp. 666-677, 1978. ↩ ↩2

-

[Holland, 1986] J. H. Holland, “Escaping Brittleness: The Possibilities of General-Purpose Learning Al gorithm Applied to Parallel Rule-Bases Systems,” Machine Learning, Vol. 2, pp. 593-623, 1986. ↩ ↩2

-

[Huhns and Bridgeland, 1991] M. N. Huhns and D. M. Bridgeland, “Multiagent Truth Maintenance,” IEEE Trans. SMC, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 1437-1445, 1991. ↩ ↩2

-

[Ishida and Stolfo, 1985] T. lshida and S. J. Stolfo, “Towards Parallel Execution of Rules in Production System Programs,” ICPP-85, pp. 568-575, 1985. ↩ ↩2

-

[Ishida, 1989] T. Ishida, “CoCo: A Multi-Agent System for Concurrent and Cooperative Operation Tasks,” International Workshop on Distributed Ar tificial Intelligence , pp. 197-213, 1989. ↩ ↩2

-

[lshida et al., 1990] T. Ishida, M. Yokoo and L. Gasser, “An organizational Approach to Adaptive Production Systems,” AAAI-90, pp. 52-58, 1990. ↩ ↩2

-

[Ishida, 1991] T. Ishida, “Parallel Firing of Produc tion System Programs,” IEEE Trans. KDE, Vol. 3, No.l, pp. 11-17, 1991. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

[Ishida and Korf, 1991] T. Ishida and R. E. Korf, “Moving Target Search,” IJCAI-91, pp. 204-210, 1991. ↩ ↩2

-

[Ishida et al., 1991] T. Ishida, Y. Sasaki and Y. Fukuhara, “Use of Procedural Programming Lan guages for Controlling Production Systems,” CAIA 91, pp. 71-75, 1991. ↩ ↩2

-

[Ishida, 1992a] T. Ishida, “Moving Target Search with Intelligence,” AAAI-9~, pp. 525-532, 1992. ↩ ↩2

-

[Ishida, 1992b] T. Ishida, “A Transaction Model for Multiagent Production Systems,” CAIA-9~, pp. 288-294, 1992. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

[Ishida et al., 1992] T. Ishida, L. Gasser and M. Yokoo, “Organization Self-Design of Distributed Production Systems,” IEEE Trans. KDE, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 123-134, 1992. ↩ ↩2

-

[Ishida et al., 1995] T. Ishida, Y. Sasaki, K. Nakata and Y. Fukuhara, “An Meta-Level Control Architec ture for Production Systems,” IEEE Trans. KDE, Vol. 7, No.l, pp. 44-52, 1995. ↩ ↩2

-

[Korf, 1990] It. E. Korf, “Real-Time Heuristic Search,” Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 42, No. 2-3, pp. 189-211. 1990. ↩ ↩2

-

[Kuwabara et al., 1995] K. Kuwahara, T. Ishida and N. Osato, “AgenTalk: Coordination Protocol De scription for Muitiagent Systems,” ICMAS-95 (The full version is available as Technical Report oflEICE, AI94-56), 1995. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

[Kuwabara, 1995] K. Kuwabara, AgenTalk 1.0 Refer ence Manual, 1995. ↩ ↩2

-

[Smith, 1980] R. G. Smith, “The Contract Net Pro tocol: High-Level Communication and Control in a Distributed Problem Solver,” IEEE Trans. Comput ers, Vol. 29, No. 12, pp. 1104-1113, 1980. ↩ ↩2

-

[Soloway et al., 1987] E. Soloway, J. Bachaut and K. Jensen, “Assessing the Maintainability of XCON-in RIME: Coping with the Problem of a VERY Large Rule-base,” AAAI-87, pp. 824-829, 1987. ↩ ↩2

-

[Watkins, 1989] C. J. C. H. Watkins, Learning from Delayed Rewards, PhD thesis, Cambridge, 1989. ↩ ↩2

-

[Yokoo et ai., 1992] M. Yokoo, E. H. Durfee, T. Ishida and K. Kuwabara, “Distributed Constraint Satisfac tion for Formalizing Distributed Problem Solving,” ICDCS-92, pp. 614-621, 1992. ↩ ↩2

↩

↩

Toru Ishida,

Toru Ishida,